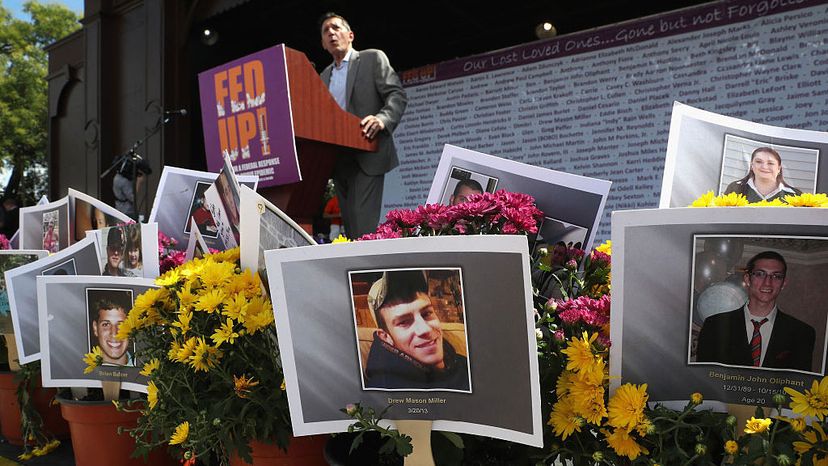

“Michael Botticelli, the former U.S. National Drug Control Policy Director, speaks at the Fed Up! rally to end the opioid epidemic in 2016 in Washington, D.C. Protesters planted signs with photos of loved ones who had died from opioid addiction. John Moore/Getty Images

“Michael Botticelli, the former U.S. National Drug Control Policy Director, speaks at the Fed Up! rally to end the opioid epidemic in 2016 in Washington, D.C. Protesters planted signs with photos of loved ones who had died from opioid addiction. John Moore/Getty Images

In October, President Donald Trump declared the opioid crisis a national public health emergency. In a much-publicized White House ceremony, an emotional Trump insisted, "Nobody has seen anything like what’s going on now," referring to the thousands of Americans overdosing each year from a class of narcotics that includes prescription painkillers, heroin and fentanyl (a synthetic form of heroin).

But we have. Back in the 1980s and early 1990s, the crack cocaine epidemic ravaged poor black communities across the country. When crack arrived in economically depressed urban areas, it proved both powerfully addictive and potentially lucrative. Violent turf wars erupted as dealers fought for control of the market, and the grip of addiction caught many people.

Treatment of Crack

The government’s response to the crack epidemic was to double-down on the "War on Drugs" first declared by Richard Nixon in 1971. In 1986, Congress passed the infamous 100-to-1 sentencing law, which treated the possession of 1 gram of crack — not the sale, mind you — as the equivalent of possessing 100 grams of powder cocaine. This was on top of a five-year mandatory minimum sentence for first-time possession of crack.

Since black people accounted for 80 percent of crack arrests, black communities were hardest hit by the ultra-criminalization of crack, which sent young black men to prison at historic rates. The federal prison population swelled from 1985 to 2000 and two-thirds of those convictions were for drug offenses. Studies have shown that although blacks are no more likely than whites to use illegal drugs, they are six-to-10 times more likely to be incarcerated for drug offenses.

“A typical media image from the War on Drugs, 1989: Police officers search through a crack house following a raid. They arrest 82-year-old Frank Wilcher (center), who was running the crack house.Steve Starr/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

“A typical media image from the War on Drugs, 1989: Police officers search through a crack house following a raid. They arrest 82-year-old Frank Wilcher (center), who was running the crack house.Steve Starr/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

Treatment of Opioids

In contrast to the "tough on crime" response to the crack epidemic, which took its toll primarily on poor black communities, the government response to the opioid crisis — in which more than 80 percent of overdose victims are white — has been wildly different, particularly in the way that elected officials and law enforcement talk about addiction.

When President Trump declared the opioid crisis a public health emergency, he talked about his brother who died from an alcohol addiction. Chris Christie, the New Jersey governor who leads Trump’s opioid task force, also talks about losing a close friend to opioid addiction.

Police departments across the country adopted treatment-first policies that postponed or forwent criminal prosecution for opioid possession and diverted drug offenders to treatment programs. Police officers in the small town of Laconia, New Hampshire, a state hit particularly hard by overdose deaths, carry business cards that read, "The Laconia Police Department recognizes that substance misuse is a disease. We understand you can’t fight this alone."

One reason that most opioid addicts are white could be because they are more likely to be prescribed pain medication. One study showed that doctors are less likely to prescribe pain medication for their black patients, believing (falsely) they had a higher pain threshold.

The Experts Weigh In

Ekow Yankah, a law professor at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law at Yeshiva University, finds this treatment-first rhetoric a little bittersweet. He says that while it’s heartening to see local law enforcement and elected officials talking about addicts as victims instead of moral degenerates, it’s not like any of it is based on new information.

"We spent two generations locking up young black men for any reason we could, in large part covered by the War on Drugs. And then we have an explosion of addiction in the white community, and suddenly everybody starts reading all the science that’s been around for two decades," says Yankah.

Yankah is one of many voices calling out the clear racial divide between the hyper-criminalization and moral outcry over crack addiction and the leniency and compassion shown toward opioid addiction. When pregnant black mothers became addicted to crack, it sparked a national panic over "crack babies." Today, a baby is born addicted to opioids every 19 minutes, but where is the vilification of "opioid moms"?

Much was made during the 2016 presidential campaign about the economic toll of globalization on rural, mostly white communities, and how the ensuing joblessness and hopelessness helped to fuel the opioid crisis. Maia Szalavitz, a New York-based journalist who has written extensively about addiction, wonders why the same connections weren’t drawn between economic depression and drug use in black communities.

"The reason we saw crack hit black neighborhoods the way it did in the ’80s and ’90s, was because they had high unemployment levels and were hit hard by deindustrialization," says Szalavitz, "all the same things we’re seeing in rural white communities now."

Yankah says that plenty of sociologists and economists were making those connections back in the 1980s, but their voices and data were drowned out by a media narrative that preferred to place the blame for the crack epidemic on negligent black mothers and absent black fathers.

"If you ask me, do I think if you changed the race of the victims, will our sympathies change?" Yankah says. "I have to say yes."

Now That’s Interesting

The "crack baby" panic of the late 1980s was sparked by one preliminary study of just 23 infants and led to predictions that an entire generation would grow up to sickly, brain damaged and heavily dependent on social services. Longitudinal studies have since exposed the crack baby myth, showing that full-term babies born to crack-addicted mothers show no health differences compared to their peers.