“More studies are revealing that people who have had COVID-19 infections are dealing with the aftermath of long-COVID symptoms. sorbetto/Getty Images

“More studies are revealing that people who have had COVID-19 infections are dealing with the aftermath of long-COVID symptoms. sorbetto/Getty Images

By now, we know the various symptoms: the fever, shortness of breath, the nausea and anosmia, the signature dry cough. Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, more than 234 million people have become intimately familiar with some combination of these telltale signs as they grappled with the coronavirus. For many, recovery began two or three weeks later.

For some COVID-19 patients, though, the symptoms have never gone away. Months after their first positive test, COVID "long-haulers" still experience splitting headaches, nerve and joint pain, fatigue, cognitive sluggishness (also known as brain fog) and occasionally distortion of smell and taste.

This experience has been dubbed "long COVID," and it’s an ongoing fight against symptoms from a virus that was supposed to have run its course. It’s become prevalent enough that the National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced a $1.15 billion, four-year initiative to study the disease in December 2020.

Let’s take a deeper look at we know about long COVID, and how doctors might go about treating it.

What Causes Long COVID?

We know that symptoms of long COVID set in after an initial infection with the coronavirus. However, scientists haven’t fully uncovered why these symptoms persist in some people, but not others. "That’s the million-dollar question," says Michael VanElzakker, Ph.D., a neuroscience researcher at Harvard Medical School.

That said, there are a few hypotheses.

The first is that the virus simply never leaves the body. Known as "viral persistence," certain viruses can take up residence in their host’s body once the acute infection cycle is finished. These renegade viruses hide out in tissues, where they may act like guerrilla fighters, causing chronic low- to mid-level symptoms punctuated by periods of dormancy.

For example, the chickenpox virus normally infects kids at a relatively young age, causing mild (if incredibly annoying) symptoms. However, the virus can stay in the infected individual’s body well into adulthood, reemerging as a nasty case of shingles. Research published in the journal Nature in September 2021 also suggests that the Ebola virus may remain in the systems of those who survive their initial infection, leading to chronic issues like muscle fatigue and an increased risk of miscarriage.

Another hypothesis is that, in certain cases, COVID-19 can lead to organ or tissue damage. Inflammation is one of your body’s natural immune responses to viruses like coronavirus. But that natural response can go haywire. For some patients, COVID-19 infection can trigger a severe, cascading inflammatory response in multiple organ systems, including the lungs, brain and blood vessels leading to what’s known as a cytokine storm. This can result in scar tissue buildup in the lungs, long-term heart complications, or even an elevated risk of stroke.

Finally, it could be the case that long COVID is triggered by other opportunistic viruses. "When there’s an acute infection, other viruses can often take advantage of that and sort of start to do their own thing," VanElzakker says. In fact, a June 2021 study in the journal Pathogens found that COVID-19 patients are more susceptible to infection by a reawakened Epstein-Barr virus — the same pathogen that causes mononucleosis.

Each of these hypotheses (and others) is being investigated by various research groups, including VanElzakker’s. However, he cautions that long COVID is likely not a one-size fits all diagnosis. "We have to be a little bit careful that we don’t consider this some unique standalone problem," he says. "It’s probably not going to be the same thing for every single person."

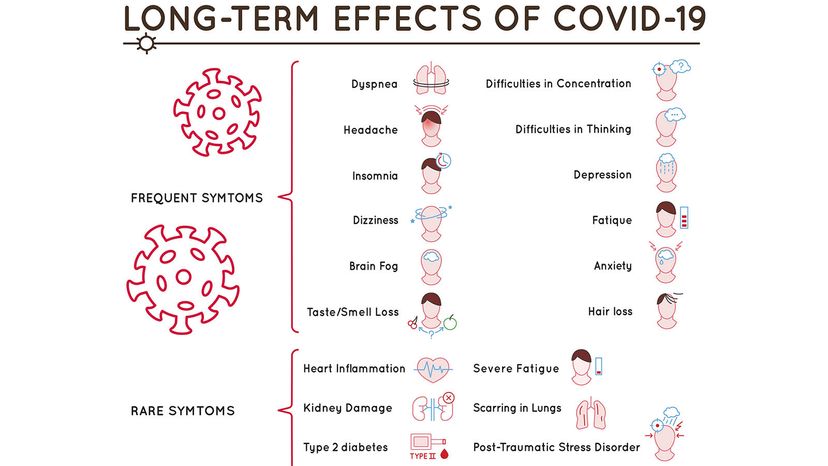

“Long-term effects of COVID-19 include shortness of breath, headache, "brain fog," insomnia, loss of taste and smell, and anxiety, among others.Double Brain/Shutterstock

“Long-term effects of COVID-19 include shortness of breath, headache, "brain fog," insomnia, loss of taste and smell, and anxiety, among others.Double Brain/Shutterstock

Who Is Most Likely to Get Long COVID?

Due to the relatively recent emergence of the novel coronavirus, it’s difficult to say with certainty who is most at risk for long COVID. But, thanks to the efforts of scientists and statisticians across the globe, a clearer picture is beginning to emerge.

In a study published Tuesday, Sept. 28, in the journal PLOS Medicine, researchers found that about 36 percent of patients studied were still experiencing symptoms COVID-like symptoms three and six months after they initially tested positive for the virus. Most previous studies have estimated lingering COVID-19 symptoms in between 10 and 30 percent of patients, including an April 2021 U.K. study of more than 20,000 COVID-19 patients, which found that 13.7 percent of participants were still experiencing symptoms at least 12 weeks after diagnosis.

The new study, which was led by scientists at the University of Oxford scientists in the United Kingdom, searched anonymized data from millions of electronic health records to identify a study group of more than 273,000 patients with COVID-19.

Survivor bias might also skew the age numbers for long COVID. A separate September 2021 study by the U.K. Office of National Statistics (ONS) found that people between the ages of 50 and 69 were most likely to report long-term symptoms, especially if they had other preexisting health conditions. But, as other research has pointed out, this might be because older folks are more likely to die from the disease.

So far, it seems that vaccination cuts the risk of developing long COVID roughly in half.

Are There Treatments for Long COVID?

Unfortunately, treatment options for long COVID are fairly limited at the moment.

"Lots of people are being affected by this," VanElzakker says. "But it’s a pretty open question." Because the source of long COVID is much trickier to pin down than an acute COVID-19 infection, it puts doctors and patients alike in a difficult bind. And without a standard treatment protocol in place, medical providers often feel helpless to recommend a course of action, while their patients continue to suffer.

The other issue is that chronic conditions are often complex and resource-intensive to treat — and they come with a certain amount of stigma. A 2010 study, published in Pain Medicine, found that 88 percent of patients who had chronic pain reported being disbelieved by their primary care provider about their experience. "It can be very frustrating," VanElzakker says.

But some hospitals, such as UCLA Health, are beginning to offer long COVID treatment plans, customized for each individual patient. Some of these plans include input from psychologists and other mental health professionals in addition to neurologists, cardiologists and infectious disease experts. Health care providers hope that these more robust mental health resources will help long COVID patients not only manage their cognitive symptoms, but also the emotional distress and fatigue that accompanies chronic illness.

"If we only focus on recovery from the virus, and not recovery from a holistic, whole-person perspective, people’s recovery is going to be incomplete," Johns Hopkins psychologist Megan Hosey said in an American Psychological Association interview.

Now That’s Interesting

Chickenpox is incredibly contagious. Before the chickenpox vaccine was added to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s recommended childhood vaccination regimen in 1995, about 4 million U.S. children contracted the disease annually. As of 2019 that number has fallen by 95 percent.